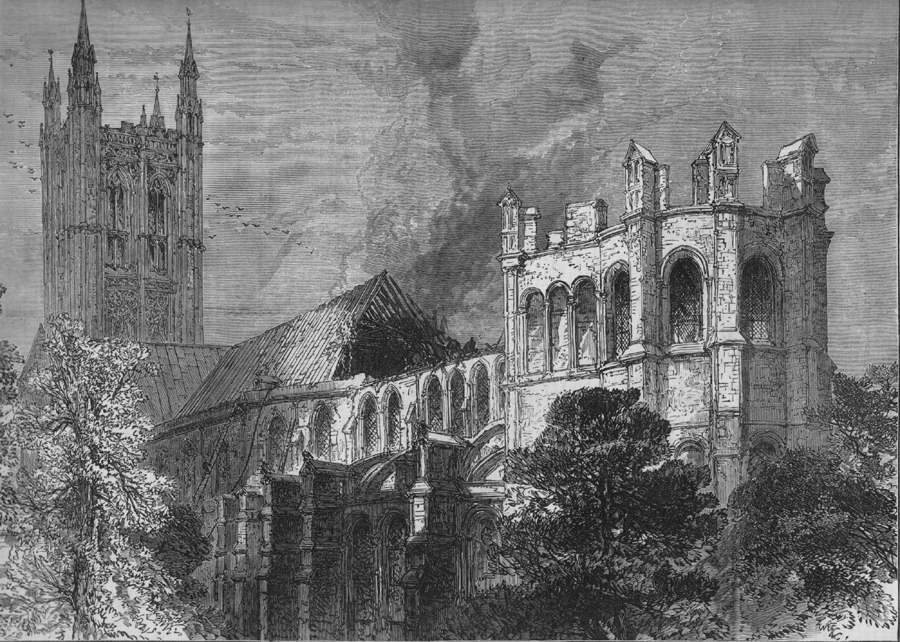

From the Illustrated London News September 14, 1872

THE FIRE IN CANTERBURY CATHEDRAL

The fire which destroyed the roof of the east end of Canterbury Cathedral, on Tuesday week, and which threatened the entire destruction of that venerable building, was mentioned in our last publication. It was caused by the upsetting of a pot of burning charcoal used by the plumbers employed to solder the leaden covering of the roof. The molten lead poured through to the woodwork below, and the roof in that part was soon on fire. It was then about half-past ten o'clock in the morning. The daily morning service had just concluded, but the choir had stayed behind to rehearse something for the afternoon. When he alarm was given he boys and lay clerks rushed from the building in their surplices, not knowing exactly the extent of the danger. The organ-blower in the meanwhile had the presence of mind to go to the tower and ring the great bell, thus making known to the city and neighbourhood something was amiss. Smoke and flames were soon seen issuing in volumes from that part of the east end of the roof near Beckett's crown, and by this time people were streaming into the precincts and viewing the conflagration in helpless dismay. It should be stated that two or three years ago very excellent waterworks were established in Canterbury, which are computed to supply the citizens with about 180,000 gallons per diem, from a reservoir on St. Thomas's-hill, and from which the service is continuous, at a pressure of 70lb to the square inch. Unfortunately, the Dean and Chapter, or their surveyor, had not yet got the hydrants of the water company fixed around the Cathedral; but the hose belonging to the Phoenix and Kent Fire Offices and to the City Volunteer Fire Brigade was of sufficient length to be affixed to the hydrants in the adjoining streets, and thence carried through the Cathedral yard to the burning building, the city brigade alone using 700 ft. for this purpose. Although the men belonging to the various brigades were on the spot as quickly as possible, it was not until twelve o'clock that any water could be got to touch the flames at all. Meanwhile the fire was gradually destroying the whole of the eastern roof. Indeed, up to this time so serious did matters look that the Vice-Dean, the Rev. Canon Thomas, telegraphed to Captain Shaw, of the steam fire-engines an order which, happily soon after had to be countermanded, as the flames were subdued. A telegram was also dispatched to Ashford for a further supply of hose, which was at once sent, with the Ashford Fire Brigade. About half-past eleven forty men belonging to the Cavalry Depot Brigade, under the command of Quartermaster Woods, and forty of the Royal Horse Artillery, marched into the precincts and rendered excellent service, both in assisting the local police to control the crowd and on the roof of the building. The hose from the Phoenix Office was the first to reach the fire, and immediately afterwards Mr. George Delassaux*, of the Canterbury Volunteer Fire Brigade, at considerable personal risk, broke his way though one of the small windows in the clerestory, and, dragging his hose after him, brought a second stream to play upon the flames. Meanwhile the burning timers, with the vane which stood at the east end, had fallen in upon the groined roof below, and sparks and molten lead were dropping through the Trinity Chapel and Beckett's shrine, at the rear of the altar. An army of volunteers was quickly pressed into service, and everything inflammable was removed from the choir, even the heavy communion-table being taken away, the altar rails torn up, and the armour and shield of the Black Prince removed from the tomb where they have hung for centuries. By one o'clock it became apparent that the force of water from the hydrants was getting the upper hand of the fire, just as it was in contemplation to cut a vast gap in the roof, and so arrest the flames. The soldiers were working well both with the hose and the axe, cutting away the burning timbers, and a two o'clock a ringing cheer went up from the men on the roof, which was heartily joined in by the crowd below, in token of the extinguishing of the fire.

The building is insured in the Sun Fire Office for £20,000, and the damage is variously estimated at from £3000 to £5000. At the spot where the fire took place is some of the most valuable stained glass to be found in the cathedral, but very fortunately none of this is injured. The beautiful mosaic pavement in front of Beckett's shrine, or St. Thomas's Chapel, has also escaped damage. But that portion of the roof which covered Trinity Chapel, at the extreme east of the edifice, extending to the canopy over the spot which indicates where once stood the shrine of St. Thomas a Beckett, and over the altar and choir, is entirely gone.

During the afternoon volunteer and other fire brigades entered the city from various neighbouring towns, but of course their services were not required. Archdeacon Harrison, Canon Thomas, and others of the cathedral body determined, shortly after the fire had been extinguished, not to abandon the afternoon service, which has been held daily without interruption during the past 300 years. To this end the immediate approaches to the building were thrown open and guarded by military and police in order that the dense volume of smoke might be allowed to escape. The hour of Divine service was altered from three to four o'clock, and at that hour, by dint of considerable exertions, the choir was made available for the accommodation of a large congregation. Archdeacon Harrision, who read the prayers, prefaced them by invoking the assembly to offer up thanks to God for his mercy in having saved the beautiful building from destruction. Subsequently a special Te Deum was solemnised, and the service throughout was of the most impressive nature.

By far the larger part of the present cathedral is the work of the Norman era, having been erected in the first half century after the Conquest, when Archbishop Lanfranc found the old cathedral in ruins, and "reconstructed from their foundation both church and monastery." Under his successor, Anselm, the eastern part of this edifice (which seems to have been only temporary in its design) was taken down and re-erected with great magnificence under the care of Ernulph, then prior of the monastery. It was finished by the next prior, Conrad, who decorated the chancel and eastern part with so much splendour that it came to be called "Conrad's glorious choir." The church was solemnly dedicated by Archbishop William, in A.D. 1130, in the presence of Henry I. of England, David King of Scotland, and all the English Bishops. It was in this building, as our readers are aware, that Beckett was murdered in A.D. 1170, and in the "choir of Conrad" his body was watched by the monks during the succeeding night. Four years later, on Sept. 5, 1174, this choir was burnt down; and we have a description of the conflagration from the pen of Gervaise, a monk of Canterbury, who was an eye witness of the event. The choir and eastern parts of the cathedral were rebuilt in 1184, the church having been closed several years. On the present occasion, we have reason to be thankful that the damage has been comparatively slight. Had the fire continued, not only "Beckett's Crown" and Henry IV.'s Chantry, and the Trinity Chapel, in which are the monuments of the Black Prince, Henry IV., Archbishop Courtenay, Cardinal Chatillon, and Dean Wotton would have perished, but the site of Beckett's shrine must have been entirely obliterated, together with the fine frescoes in the adjoining transept; an the tomb of Cardinal Pole, the last Archbishop interred in the cathedral, would have undergone the same fate.

Photographs of the effects of this fire were taken on the same day by Messrs. Barnes and Son, of Mile-end-road.

In the 1870's George H. Delasaux age 24 was living at home with his father Thomas P. DeLasaux widower, who is a Wine & Spirit Merchant. They were living at 30 High Street in All Saints, Canterbury. George is noted as unemployed.