![]()

~ CANTERBURY CEMETERIES ~

CANTERBURY, KENT

I cannot explain why I find the Canterbury graveyards so captivating, maybe it's the growing realization of my own mortality, or the hope that one day I'll find that elusive Terry gravestone. The monuments fascinate me and even though they are not members of my family, I care about their lives and their history, these people are part of what made Canterbury such a great city. Some of the monumental inscriptions make me smile, some break my heart, and some make me cry, but each one holds an actual bit of history and a deep connection to Canterbury itself.

Some stones are toppled and broken, some are completely overgrown with bushes or covered in moss, many have been removed, and some have sadly been defaced. This lack of care for our ancestors in the graveyards is very disappointing, there should be a society created for the future welfare of these historic places. I'm certain that in the last 90 years with all of the environmental polution that our population has produced it has effected many of the stones which are now very worn and almost unreadable. I'd like to thank historians like Joseph Meadows Cowper for all his hard work in documenting the monuments of the city in the late 1800's, which helped me in sorting many of these out. I'd also like to thank the people that are working on a special x-ray type of photography that one day may bring these impossible to read stones back to life.

My hope is that you may find what you are looking for here, that little missing piece of your family history that makes your story more complete.

Good luck in your search!!

"Also in Canterbury, burials to be discontinued forthwith in the following churches and chapels, and from and after the first January, one thousand eight hundred and fifty-six, in the burial-grounds thereof, viz.: The Cathedral, All Saints, St. Mary de Castro, St. Mildred, St. Peter, Holy Cross Westgate, St. Margaret, St. Mary Bredin (two burial-grounds) St. George the Martyr, St. Alphage (two burial-grounds) St. Mary Northgate, the Wesleyan Chapel in the parish of St. Peter, the Countess of Huntingdon's Chapel, in the parish of St. Mary Bredin, and the Independent Chapel Orange-street, and Unitarian Baptist Chapel, both in the parish of St. Alphage. To be discontinued forthwith in the churches of St. Dunstan and St. Gregory the Great. To be discontinued forthwith within three yards of all dwelling-houses in the Friends' Burial-ground in St. Dunstan's parish. In the burial-ground of St. Gregory the Great, and in the Canterbury Cemetery in the parish of Thannington, burials to be conducted according to the regulations for a new burial-grounds provided under the Burial Acts."

Bulletins and Other State Intelligence 1855

Most churches also had their own burial grounds alongside or near them:

ST. MARY DE CASTRO

ST. ALPHAGE

A view of the cemetery attached to St. Alphage church in St. Alphage lane

HOLY CROSS WESTGATE

MEMORIAL INSCRIPTIONS

Inscriptions inside Holy Cross Church from J. M. Cowper

Inscriptions from Holy Cross Churchyard from J. M. Cowper

ST. PAUL'S

ST. PAUL'S CEMETERY (complete)

ST. MARTIN'S

ST. MILDRED'S

THE CLOISTERS, CANTERBURY CATHEDRAL

Views of the Cloister Graveyard, Canterbury Cathedral

ST. DUNSTAN'S

St. Dunstan's Church and Burial Ground

CANTERBURY CEMETERY

CANTERBURY CEMETERY, WHITSTABLE ROAD

WINCHEAP

From hence, entering the city again through Wincheap gap, we pass over Chapel yard, the burying place of three parishes in the city, which have no ground belonging to them, down Castle street, and across Watling street to St. Margaret's church in which is an ecclesiastical court.... The Kentish Travellers Companion 1776

WINCHEAP NON CONFORMIST BURIAL GROUND

ST. GREGORY THE GREAT

The Military Cemetery was removed and a playground now covers the area

ST. GREGORY THE GREAT GRAVEYARD

"St. Gregory's Priory - an extensive burying-ground was attached to it, not appropriate to the hospital alone, but to the parishioners of Northgate."

Canterbury in the Olden Time, second edition, John Brent, F.S.A. 1879

ST. MARY NORTHGATE

ST. MARY NORTHGATE, BURIAL GROUND, BROAD STREET (Complete)

"At the further end of this suburb, on the right hand, at the entrance of the road to Whitstaple, is a burial place for the Jews; and another, not far from it, for the Quakers." HT1793

JEWISH CEMEMTERY

ALL SAINTS

ALL SAINTS GRAVEYARD (Complete)

ST. MARY MAGDALEN (burial ground was part of St. George the Martyr)

ST. MARY BREDIN (two burial grounds) they no longer exist

ST. PETER'S

ST. GEORGE THE MARTYR (burial ground has been built upon, was to the north and east of the church) no longer exists

ST. MARGARET'S

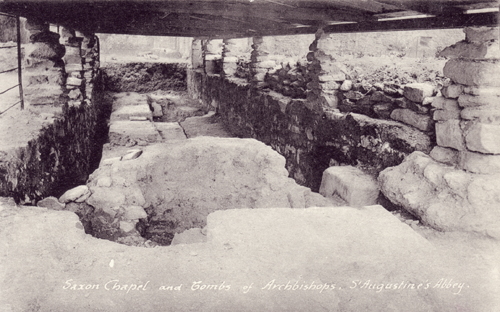

ST. AUGUSTINE'S ABBEY

"It likewise retained for about one hundred years, that is till the days of Archbishop Brightwald, the exclusive right of being the cemetery for the kings, and, till the time of Cuthbert, that of the archbishops; this, besides the honour, was attended with many solid advantages."

Grose's Antiquities of England and Wales, Vol. III., 1787 (Francis Grose Esq. F.A.S.)

"When this cemetery was ransacked some years since in search of the stone coffins, several were dug up with skeletons in them, among which were some of the religious, they were all entire, and lay at a depth of about seven feet. Great quantities of human bones besides were dug up of different sizes and at different depths; the stones which composed the coffins being carried off, the bones they contained were thrown into the ground at random, but the indecency of this was so flagrant, that a stop was put to the farther progress of it. The greatest part of this cemetery has been demised to the trustees of the Kent and Canterbury Hospital, which has been built on part of it, in digging the foundation for which, the workmen, from the depth of from one to six feet, were much incommoded by a great quantity of human bones and skulls, which lay in a promiscuous manner, and not the least remains of any coffin near them, so that they much have been greatly disturbed since their first interment. Near the place were some hollows in the earth resembling the human shape, which certainly once contained entire bodies, though when removed is not known. In 1837, the men engaged in the improvements of the Hospital discovered a leaden coffin of rude workmanship, containing a skeleton; public curiosity was much excited, and it being stated that the coffin would be opened on a certain day, a large concourse of people assembled to witness it; but after waiting for some hours in anxious expectation, they were informed that the powers that were, had determined that it should not be opened, which caused much disappointment. We doubt, however, if the curious crowd suffered any great loss, excepting that of their time." CG1843

*the great quantity of human skulls and bones they found "which lay in a promiscuous manner" could have been bodies that were put there during the plague (just like some places in London) my notes

"..it being prohibited by the law of the twelve tables* to bury in the cities."

Grose's Antiquities of England and Wales, Vol. III, 1787

*the twelve tables are ancient Roman laws "No dead man may be cremated nor buried in the City"

"The custom of burying bodies in churches is said to have been first sanctioned by Cuthbert, Archbishop of Canterbury, A.D. 758, having been prohibited by Augustine, the first Archbishop of that church, who had decreed that no corpse, either of prince or prelate, should be buried within the walls of a city; but only in the suburbs thereof; and that only in the porch of a church, not in the body." The Saturday Magazine 1833

"One cemetary on the east, runs under and on both sides of the road now called "Old Dover Road;" part of it was subsequently used as the graveyard of St. Sepulchre's Nunnery. A second Roman cemetery was found outside Worth Gate. It was adjacent to the site of the Chatham and Dover Railway Station, and extended into Wincheap field, beyond the Gasometer. A third cemetery was on the St. Dunstan's Road. It included the site of St. Dunstan's Churchyard, but it extended from the South Eastern Railway cutting to the London Road on the north-west. A fourth cemetery was found a Vauxhall, beside the Ramsgate Road. It included the sites of the Infantry and Cavalry Barracks. A fifth seems to have been near Little Barton and the cemetery of St. Augustine's Abbey. (See Brent's Canterbury in the Olden Time, 2nd Edition, pp. 31-33, 38-41)

The Roman road was found throughout Beer Cart Lane; but in Watling Street it runs under the houses on the north side of the street, not beneath the roadway. It also ran considerably to the north of Old Dover Road, not beneath the present roadway there. "Archaeologia Cantiana, 1883"

"The very evil custom of interring the dead in and near the places devoted to public worship is, to the best of our knowledge, peculiar to Christian countries. Its introduction seems to have been very early; for we find interments within cities altogether prohibited by an edict of the Emperor Theodosius, in which it is very truly stated that such a practice is injurious to the public health, while monuments by the way-side present salutary memorials to the traveller. A person infringing this law forfeited a third of his patrimony; and an undertaker directing a funeral contrary to this prohibition was fined forty pounds of gold.

But when the churches were built over the bodies or ashes of saints and martyrs, or their remains were translated to the churches, a strong desire began to be felt that the dead should receive the protection and benefit of such sacred neighbourhoods. Therefore, first the clergy, then kings and persons of rank, and at last the common people, were interred at first round about the church, then in open places attached to the outward wall, which were called "Galilees," and at last within the church itself. The facility which the proximity of the graves to the churches afforded the clergy in performing the customary rites for the dead, not a little contributed to the introduction and continuance of the custom. It is said to have been introduced into this country from Rome about the middle of the eighth century, by Cuthbert, archbishop of Canterbury, so far as churchyard cemeteries are concerned. Lanfranc, also archbishop of Canterbury, is stated to have been the first who brought in the practice of vaults in chancels, and under the very altars, when he had rebuilt the church of Canterbury, about the year 1075. But there is no doubt that graves in churches, for the clergy at least, existed at a much earlier period in this country; witness the story of the re-appearance of St. Dunstan, to complain of the annoyance he underwent from the interment of the son of Earl Harold in the same church with him. However, from the time of Lanfranc, the practice seems to have prevailed in London without interruption until the Great Fire in 1666, which effected a very complete destruction of the churches, and, together with them, of the contents of the vaults and churchyards attached to them. The evil of the practice had become apparent before that event, and considerate people lamented that advantage was not taken of the calamity to introduce a better system. "I cannot but deplore," says Evelyn in his "Sylva," "that when that spacious area was so long a ras tabula, the church-yards had not been banished to the north walls of the city, where a grated inclosure, of competent breadth for a mile in length, might have served for an universal cemetery to all the parishes, distinguished by the like separations, and with ample walks of trees, the walks adorned with monuments, inscriptions, and titles, apt for contemplation and memory of the defunct." That this, or something like this was not then done cannot seem very surprising, when we perceive that, at this more enlightened day, people exhibit no great alacrity in availing themselves of the advantages somewhat resembling those which the excellent Evelyn wished to afford." The Penny Magazine 1834

The Romans introduced into Britain their Law of the Ten Tables, by which it was ordained that "all burnings or burials" should be "beyond the city,"[3] and the system continued to prevail long after the Roman evacuation. It was not until A.D. 742 that Cuthbert, eleventh Archbishop of Canterbury, brought from Rome the newer custom of burying around the churches, and was granted a Papal dispensation for the practice. The churchyards even then were not enclosed, but it was usual to mark their sacred character by erecting stone crosses, many of which, or their remains, are still in existence. Yet it was a long time before churchyard interments became general, the inhabitants clinging to the Pagan abit of indiscriminate burial in their accustomed places. We hear nothing of headstones in the early days of Christianity, but there are occasionally found in certain localities inscribed stones which bear the appearance of rude memorials, and these have been regarded as relics of our National Church in its primitive state. It is also suggested that these stones may be of Druidical origin, but there is nothing to support the theory. Among the aboriginal Britons the custom of simple inhumation was probably prevalent, but there are not wanting evidences in support of the belief that cremation also was sometimes practised in prehistoric times. An instance of early interment was discovered in a tumulus at Gusthorp, near Scarborough, in 1834. In a rude coffin scooped out of the trunk of an oak-tree lay a human skeleton, which had been wrapped or clothed in the skin of some wild animal, fastened at the breast with a pin or skewer of wood. In the coffin were also a bronze spearhead and several weapons of flint--facts which all go to establish a remote date. The absence of pottery is also indicative of a very early period. Regarding the skins, however, it may be remarked that Caesar says of the Britons, when he invaded the island, that "the greater part within the country go clad in skins."

Christian burials, as we have seen, cannot be dated in England earlier than the eighth century, and monuments at the grave may have possibly originated about the same period, but there is nothing whatever to sustain such a belief, and we cannot assign the earliest of existing memorials to a time prior to the eleventh century. Indeed it is very significant to find that the tombs within the churches are only a trifle older than the gravestones outside, scarcely any of them being antecedent to the sixteenth century. As burials inside churches were not permitted until long after the churchyards were used for the purpose,[4] it is indeed possible that no memorials were placed in the edifice until Tudor days; but this is scarcely feasible, and the more probable explanation is that all the earlier ones have disappeared.

In search of Gravestones Old and Curious 1896

(3) The ancient Jewish burial-ground had to be no less than 2000 cubits (or about a mile) from the Levitical city.

(4) The unhealthy practice of using churches for this purpose was continued some way into the nineteenth century. The still more objectionable plan of depositing coffins containing the dead in vaults under churches still lingers on. In 1875 I attended the funeral (so-called) of a public man, whose coffin was borne into the vaults of a town church, and left there, with scores of others piled in heaps in recesses which looked like wine-cellars. Not one of the many mourners who shared in that experience failed to feel horrified at the thought of such a fate. Some of the old coffins were tumbling to pieces, and the odour of the place was beyond description. In the words of Edmund Burke: "I would rather sleep in the southern corner of a country churchyard than in the tomb of the Capulets."

"Cuthbert, archbishop of Canterbury, obtained permission, about 750, for cemeteries to be made within cities; and from this circumstance some have supposed that church-yards were then first formed around the places of worship. Mr. Whitaker, however, in his History of Manchester, observes "The custom of placing cemeteries around our churches, in England, is asserted by all our antiquaries to have been originally introduced by Cuthbert, archbishop of Canterbury, about the year 750. But they are as much mistaken in this, as I have already shown them to be in many other particulars. And the church-yard was every where laid out, at the time when the parish church was erected, among the kingdoms of the heptarchy. The churches in France had cemeteries about them, as early as 595; and those in England had them equally as early as the period of their own construction. The very first that was built by the Saxons in the kingdom, that of St. Peter and St. Paul, without the city of Canterbury, had an enclosure for sepulture about it; and the very first apostle of the Saxons, the pious and worthy Augustine, was actually buried within in." Cyclopedia of Architecture...Robert Stuart 1854